It’s an obvious point, but credit cards in America

generate a lot of cash for banks. In 2022, I wrote up how the

business works, with the observation that the industry generates close to a

quarter trillion dollars a year in revenue. This revenue comes from fees for

connecting merchants and banks, as well as fees charged to consumers for access

to credit.

Every credit card network is also a data sieve, connected to

advertising data brokers, anti-fraud features, and analytics firms. In

addition, being able to reject someone from the payments system is a core

sovereign power, and the stated reason the right is so afraid of a central bank

digital currency.

There are many barriers to entry in the credit card business, and

significant pricing power among incumbents. As the Consumer Financial

Protection Bureau found, margins for credit cards are persistent, increasing,

high, and tilted towards the larger firms in the

industry. (And this is true even when you take higher interest rates

into account.)

Capital One’s recently announced attempt to buy the

credit card company Discover hits at all of these elements of the business.

While the merger looks like a credit card bank buying another credit card bank

— and it’s certainly that — it is more like a Big Tech merger, where a bank is

trying to turn itself into a platform with an app store-like power over a class

of customers, in this case merchants. The key quote from Capital One co-founder

and CEO Richard Fairbank on the call announcing the deal was this: “The holy

grail is to be an issuer with our own network.”

Here’s what Fairbank meant. An issuer, aka a bank, is regulated

like a bank, while a credit card network is regulated like a network, which

includes price caps on debit cards. But thanks to the Fed, a bank that owns a

network isn’t regulated at all on its own network. And because of that, Capital

One, if allowed to buy Discover, can set prices in ways its rivals can’t.

Fairbank also made clear that’s a key rationale for the deal, as I’ll discuss

after I’ve explained the industry and the regulatory framework.

Let’s start with the basics of credit/debit cards. Banks make

money in two ways. They issue cards to consumers, and charge those consumers

credit card interest charges and various fees when they buy things with

merchants and don’t pay the money back immediately.

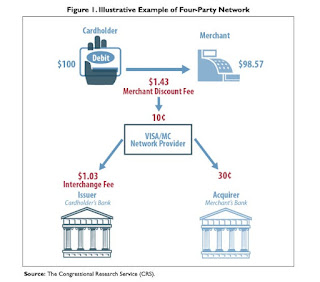

But banks also make money from the merchants themselves. In

between the bank and merchants sits a network utility, usually Visa or

Mastercard. The network operator takes a swipe fee, known as an ‘interchange

fee,’ from the merchant, roughly 1.5 to 3.5 percent of every transaction, and

then splits that fee with the banks. Banks send some of that money back to the

consumer in the form of rewards to keep consumers locked into using that

card.

There’s a difference between American Express and

Visa or Mastercard. The latter two don’t issue their own cards, banks issue

them. Conversely, banks don’t issue American Express cards, only American

Express does that. So American Express isn’t a standard credit card network. It

is technically a ‘three-party system,’ between consumers, merchants, and

American Express itself. This distinction matters for legal reasons. (Though

American Express’ status as a three-party network isn’t strictly accurate, U.S.

Bank does issue credit cards that operate on AMEX.)

So what is Discover? Well, it’s both a

normal network and a three-party system. Like Visa and Mastercard, Discover

allows banks to issue Discover cards. But like American Express, it also issues

its own credit cards.

So why does any of this matter? Well,

America’s credit card system is a massive extraction machine for middlemen, and

this merger is part of a knife-fight over who can get the biggest piece. Nowhere else in the world is

there a payments system in which 1.5 to 3.5 percent of trillions of dollars of

transactions goes to a set of middlemen, but that’s how credit cards work in

America, much to the chagrin of merchants, both small ones and the giants like

Walmart.

Network fees are excessive because

Visa, Mastercard, American Express, and Discover have market power over

merchants, who must accept the cards their customers would like to use, even if

the fee those merchants have to pay is excessive.

In 2010, Congress actually noticed

this was a problem, Senator Dick Durbin attached an amendment to the Dodd-Frank

Act which regulated these networks. Specifically, the Durbin Amendment did two

things. It had the Fed impose a price cap on swipe fees for debit cards, and it

allowed merchants to choose among debit networks for processing debit

payments.

While the Fed tilted the rules as far

as it could towards banks, the Durbin amendment has delivered somewhat

for merchants. (The Durbin Amendment only addressed debit cards, not credit

cards, and so it left out large chunks of the market. There’s now Senate

legislation, called the Credit Card Competition Act, which would allow merchants to

choose among multiple payment networks for credit cards.)

But the Fed also punched a hole in the

Durbin Amendment. When writing the rule, the Fed went along with lobbying from American Express, and in

its 2010 rules exempted three-party

networks from regulation, only applying it to Visa and Mastercard. And this

brings me back to Capital One, whose CEO made this point explicitly on the

investor call announcing its attempt to buy Discover. Here’s Fairbank:

The Durbin debit rules, intentionally

and by design only applied in networks like Visa and MasterCard who negotiate

with merchants on behalf of thousands of banks, including negotiating terms and

pricing. Discover like American Express deals directly with merchants without

an intermediary. They are both the issuer and the network, so there is nobody

in between. The Durbin debit rules were written to explicitly exclude networks

like Discover and American Express.

Fairbank also noted that their

intention is to move Capital One’s debit portfolio immediately into Discover,

though it will only move part of its credit business. As Digital

Transactions Magazine put it, “Fairbank called

out a pricing advantage of the planned move into debit.” After this merger,

Capital One will have millions of merchants at its mercy, merchants who will

have the choice to either lose customers who want to use Discover, or accept

higher fees and more intrusive rules from Capital One.

Of course, there are other reasons for

the deal. Capital One will gain a funding advantage as a bank and become Too

Big to Fail if it acquires Discover. Additionally, Discover is a large issuer

of credit cards, and the bigger the credit card issuer, the higher the prices banks

tend to charge. If Capital One buys Discover, it’ll jump to the number-one

largest credit card issuer. But the pricing power it will acquire as the owner

of Discover is a core stated reason for the merger.

And to underscore the point about

barriers to entry, Fairbank also made that clear when he told investors about

his lust for Discover’s network, saying that “we all kind of revel in the fact

that a network is a very, very rare asset. There are very few of them. And it’s

just, you know, I don’t think people are going to be building any of these

anytime soon.”

That’s not stating outright that the

goal is monopolization, but it’s pretty close.

So will the merger go through? The

deal has already drawn high-profile opposition from both sides of the aisle, as

the American Prospect reports:

Several advocacy groups have come out

against the merger proposal, including the National Community Reinvestment

Coalition, which has fought Capital One in particular for

several years. Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.) said on Wednesday that the deal

should be blocked, joining Sen. Elizabeth Warren, who opposed the merger a day earlier.

Under the current administration, it’s

hard to see a clear path for approval. The Federal Reserve and Office of

Comptroller of the Currency would have to allow the deal, and then the

Antitrust Division would have to give a green light. The Fed and the OCC are

weak, but they are also embarrassed.

And given the CEO stated on the

acquisition call that the ability to raise prices and reduce competition

through a regulatory loophole is one of the key reasons for the deal, the

Antitrust Division strikes me as an unlikely ally of the deal. As Steptoe lawyer

Stephen Aschettino put it, “I think antitrust is probably first and foremost on

the list of hurdles that Capital One is going to have to get past, and that

could take a while.”

That said, in many ways this deal is

contingent upon the election. If there’s a change in administration, then there

will be a different set of bank regulators and antitrust enforcers. It’s not

clear what happens then. In his first term, Donald Trump was lax about banking

consolidation, though his Antitrust Division did sue to stop the Visa

merger with Plaid.

So one could see this deal as a bet on

Biden losing. But I think that’s overthinking it a bit, since there’s no reason

Capital One couldn’t just wait until after the election to announce the deal.

Capital One CEO Fairbank is known as a super aggressive operator; he has

already been fined for

violating antitrust laws multiple times.

If I had to guess, I’d say this one’s

about ego, as many of these mergers are. Fairbank is a billionaire, and so he

won’t be dislodged from his position as CEO regardless of whether he has to

walk away from the deal. He’s probably thinking, swing for the fences, the

worst that happens is you strike out.

But what this deal really shows is

that the U.S. payments system is ripe for genuine reform, whether that’s

through the Fed making its public payments system, called FedNow, workable, or

Congress enacting more rules mandating competition in payments. Regardless, you

shouldn’t become a billionaire by grifting on payment fees that no other

country in the world tolerates. And a merger to enable further bloat and

consolidation isn’t the way out.

-Matt Stoller

Editor’s note: This story was originally printed on Matt Stoller’s newsletter BIG, where

he explores the politics of monopoly power.

The Lever is a nonpartisan, reader-supported investigative news outlet that

holds accountable the people and corporations manipulating the levers of power.

The organization was founded in 2020 by David Sirota, an award-winning

journalist and Oscar-nominated writer who served as the presidential campaign

speechwriter for Bernie Sanders.

Source URL: https://portside.org/2024-03-02/fed-behind-credit-card-merger

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.