[Yesterday] the Supreme Court handed down a decision in Students for

Fair Admissions, Inc., v. President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Students for Fair Admissions is an organization designed to fight against

affirmative action in college admissions, and [yesterday] it achieved its goal: the Supreme Court

decided that policies at Harvard and the University of North Carolina that

consider race as a factor in admissions are unconstitutional because they

violate the guarantee of equal protection before the law, established by the Fourteenth

Amendment.

The deciding votes were 6 to 2 in the case of Harvard—Justice

Ketanji Brown Jackson recused herself because she had been a member of

Harvard’s board of overseers—and 6 to 3 in the case of the University of North

Carolina.

In the case of the two schools at the center of this Supreme

Court decision, admissions officers initially evaluated students on a number of

categories. Harvard used six: academic, extracurricular, athletic, school

support, personal, and overall. Then, after the officers identified an initial

pool of applicants who were all qualified for admission, they cut down the list

to a final class. At Harvard, those on the list to be cut were evaluated on

four criteria: legacy status, recruited athlete status, financial aid eligibility,

and race. [Yesterday],

the Supreme Court ruled that considering race as a factor in that categorical

fashion is unconstitutional.

The court did not rule that race could not be considered at all.

In the majority decision, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote that “nothing in

this opinion should be construed as prohibiting universities from considering

an applicant’s discussion of how race affected his or her life, be it through

discrimination, inspiration, or otherwise.”

How much this will matter for colleges and universities is

unclear. Journalist James Fallows pointed out that there are between 3,500 and

5,500 colleges in the U.S. and all but 100 of them admit more than 50% of the

students who apply. Only about 70 admit fewer than a third of all applicants.

That is, according to a study by the Pew Research Center, “the great majority

of schools, where most Americans get their postsecondary education, admit most

of the people who apply to them.”

The changing demographics of the country are also changing student

populations. As an example, in 2022, more than 33% of the students at the

University of Texas at Austin, which automatically admits any Texas high school

student in the top 6% of their class, were from historically underrepresented

populations. And universities that value diversity may continue to try to

create a diverse student body.

But in the past, when schools have eliminated affirmative

action, Black student numbers have dropped off, both because of changes in

admission policies and because Black students have felt unwelcome in those

schools. This matters to the larger pattern of American society. As Black and

Brown students are cut off from elite universities, they are also cut off from

the pipeline to elite graduate schools and jobs.

More is at stake in this case than affirmative action in

university admissions. The decision involves the central question of whether

the law is colorblind or whether it can be used to fix long-standing racial

inequality. Does the Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868 to enable the

federal government to overrule state laws that discriminated against Black

Americans, allow the courts to enforce measures to address historic

discrimination?

Those joining the majority in the decision say no. They insist

that the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment after the Civil War intended only

that it would make men of all races equal before the law, and that considering

race in college admissions undermines that principle by using race in a

negative manner, involving racial stereotyping (by considering race by

category), and lacking an endpoint. “Many universities have for too long

wrongly concluded that the touchstone of an individual’s identity is not

challenges bested, skills built, or lessons learned, but the color of their skin.

This Nation’s constitutional history does not tolerate that choice,” the

majority opinion reads.

In a concurring opinion, Justice Clarence Thomas wrote that

affirmative action actually made racial tensions worse because it “highlights

our racial differences with pernicious effect,” prolonging “the asserted need

for racial discrimination.” He wrote: “under our Constitution, race is

irrelevant.” “The great failure of this country was slavery and its progeny,”

Thomas wrote. “And, the tragic failure of this Court was its misinterpretation

of the Reconstruction Amendments.”

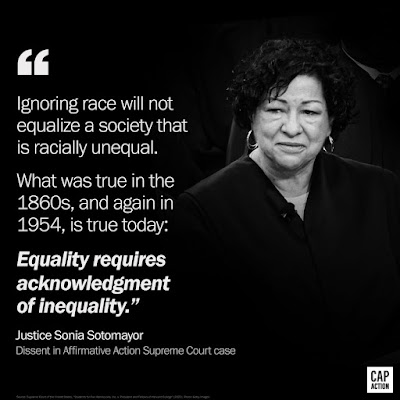

Those justices who dissented—Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, and Ketanji Brown Jackson—pointed to the profound racial discrimination that continued after the Civil War and insist that the law has the power to address that discrimination in order to achieve the equality promised by the Fourteenth Amendment.

“The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

enshrines a guarantee of racial equality,” Sotomayor’s opinion begins. “The

Court long ago concluded that this guarantee can be enforced through

race-conscious means in a society that is not, and has never been,

colorblind.”

In her concurring opinion concerning the UNC case, Jackson noted

that “[g]ulf-sized race-based gaps exist with respect to the health, wealth,

and well-being of American citizens. They were created in the distant past, but

have indisputably been passed down to the present day through the generations.

Every moment these gaps persist is a moment in which this great country falls

short of actualizing one of its foundational principles—the ‘self-evident’

truth that all of us are created equal.”

If this fight sounds political, it should. It mirrors the

current political climate in which right-wing activists reject the idea of

systemic racism that the U.S. has acknowledged and addressed in the law since

the 1950s. They do not believe that the Fourteenth Amendment supports the civil

rights legislation that tries to guarantee equality for historically

marginalized populations, and in [yesterday's] decision the current right-wing majority on the court demonstrated that it is

willing to push that political agenda at the expense of settled law. As

recently as 2016, the court reaffirmed that affirmative action, used since the 1960s,

is constitutional. [Yesterday's] court just threw that out.

The split in the court focused on history, and the participants’

anger was palpable and personal. Thomas claimed that “[a]s [Jackson] sees

things, we are all inexorably trapped in a fundamentally racist society, with

the original sin of slavery and the historical subjugation of black Americans

still determining our lives today.”

Her solution, he writes, “is to unquestioningly accede to the view of elite

experts and reallocate society’s riches by racial means as necessary to ‘level

the playing field,’ all as judged by racial metrics…. I strongly

disagree.”

Jackson responded that “Justice Thomas’s prolonged

attack…responds to a dissent I did not write in order to assail an admissions

program that is not the one UNC has crafted.”

She noted that Black Americans had always simply wanted the same right to take care of themselves that white Americans had enjoyed, but it had been denied them. She recounted the nation’s long history of racial discrimination and excoriated the majority for pretending it didn’t exist.

“With

let-them-eat-cake obliviousness, [yesterday], the majority pulls the ripcord and announces ‘colorblindness for all’ by legal

fiat. But deeming race irrelevant in law does not make it so in life. And

having so detached itself from this country’s actual past and present

experiences, the Court has now been lured into interfering with the crucial

work that UNC and other institutions of higher learning are doing to solve

America’s real-world problems.”

“[Yesterday],

the Supreme Court upended decades of precedent that enabled America’s colleges

and universities to build vibrant diverse environments where students are

prepared to lead and learn from one another,” the Biden administration said in

a statement, warning that “the Court’s decision threatens to move the country

backwards.” In a speech to reporters, Biden called for new standards that take

into consideration the adversity—including poverty—a student has overcome when

selecting among qualified candidates, a system that would work “for everyone…

from Appalachia to Atlanta and far beyond.”

“While the Court can render a decision, it cannot change what

America stands for.”

—Heather Cox Richardson

Notes:

https://www.collegetransitions.com/college-selectivity/

https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2023/06/29/affirmative-action-scotus-decision-full-text-pdf/

Twitter:

AshaRangappa_/status/1674437450851049472

neal_katyal/status/1674422760519659520

JamesFallows/status/1674472046464475138