30 Tricks Sellers Use to Make You Pay Too Much

Shop around. That’s Checkbook’s Golden Rule. The only way to make sure you’re not paying too much for anything is to compare prices from several sellers.

For more than 40 years, our undercover shoppers have obtained more than one million prices for everything from alternators to zucchini from hundreds of types of retailers and service providers—all types of home improvement contractors, auto repair shops, stores selling big-ticket products, dentists, veterinarians, travel sites, grocery stores, and many more.

This research constantly reveals huge company-to-company price differences: Some places charge more than double what their nearby competitors charge for the exact same work or products. And we find you don’t have to pay more to get good service and the best products. Companies rated highest in our surveys of consumers are just as likely to offer low prices as those that get lousy ratings. In other words, you don’t necessarily get what you pay for.

One reason for big price differences is that, because companies know most customers won’t bother to shop around, they can offer whatever prices they want. Sometimes consumers don’t shop around because it’s a pain to scour the internet for the lowest price on a TV or to schedule four or five roofers to bid on a reroofing job. But often we find buyers don’t compare prices because they’ve been duped into thinking they’re already getting a great deal.

Companies use an arsenal of marketing tricks to convince customers they’re scoring bargains, often duping them into spending more or paying right away without checking the competition. While many of these tactics have been used for centuries, we’re finding that the methods are increasingly sophisticated and the dishonest claims are bolder.

Here are 30 sneaky pricing and selling strategies to guard against. Be aware that some companies employ more than one.

Fake Sales

“SALE! 60% OFF!!”

Many retailers constantly advertise big savings. But these promotions usually aren’t discounts at all—they’re attempts to mislead.

Our researchers tracked prices of big-ticket items sold at 19 major retailers for 10 months. They found that sale prices at 17 of the stores were bogus, with supposedly lower prices being offered more than half the time. At some stores the fake sales never end: For several chains, Checkbook found most items we tracked were offered at a false discount every week or almost every week we checked. In other words, the “regular price” shown on price tags is seldom—if ever—what customers actually pay.

While some stores employ more egregious fake-sale practices than others, nearly all those we reviewed were guilty of some sales-price chicanery. Of the 19, only Costco and Bed Bath & Beyond consistently conducted legitimate sales. The other 17 retailers—including Best Buy, Gap, Home Depot, JCPenney, Kohl’s, Lowe’s, Macy’s, Target, Sears, Walmart, and others—as a group marked their items “on sale” 57 percent of the time, meaning that they were promoting fake deals more than half of the time.

These special-but-not-really-special discounts, holiday sales, and red-dot-spring/summer/whatever events are meant to manipulate you into buying items right away while “on sale” lest you soon face higher prices. It dissuades you from shopping around—after all, if something is “60 percent off,” what’s the point of comparing prices elsewhere? All this good-deal euphoria is also designed to make you snap up more stuff while you’re at it.

By constantly offering items at sale prices—and rarely or ever at regular prices—retailers are using illegal advertising. Unfortunately, the Federal Trade Commission has chosen not to enforce its own rules against such deceptive pricing.

Inflated Anchor Prices

Inflated Anchor Prices

Fake “regular” prices, referred to in the industry as “anchor prices,” enable misleading sales. Most sellers now show prices that are crossed out with lower “sale” prices splashed nearby. Those crossed-out higher “list” prices are rarely if ever charged by the store or its competitors; they’re gimmicks to make that day’s prices seem like bargains.

Few retailers prominently disclose the sources of anchor prices they display. Amazon labels any crossed-out price on its site a “List price”; if you search for the fine print, it says that’s the “suggested retail price of a product as provided by a manufacturer, supplier, or seller.”

All car dealers inflate each vehicle’s value by prominently displaying MSRP [manufacturer suggested retail price] or a “sticker” price—rarely what buyers pay.

We have problems with all false regular-price claims, but the approach used by Amazon and car dealers seems almost reasonable compared to Kohl’s. Buried in the legalese section of its website, it outrageously explains its anchor prices: “The ‘Regular’ or ‘Original’ price of an item is the former or future offered price for the item or a comparable item by Kohl’s or another retailer. Actual sales may not have been made at the ‘Regular’ or ‘Original’ prices.”

That’s right: Kohl’s is telling you that its competitors might at some point in the future charge the imaginary prices it uses to anchor its misleading “discounts.”

Like fake sales practices, this is illegal. By law, sellers are prevented from displaying crossed-out “regular” prices if they’re not actually their normally offered prices. Unfortunately, use of fake anchor prices is a standard tactic for many types of businesses now.

Scarcity Warnings

Demand is high! Supply is low! Act quickly or they won’t have anything left to sell you. Usually, it’s a ruse to push you into buying.

For example, Checkbook’s researchers spent weeks searching various hotel booking websites. At Agoda, Booking.com, Expedia, Hotels.com, Hotwire, Orbitz, Priceline, and Travelocity, we were often warned in search results about sold-out hotels or “Only 1 Left.” The design of each website constantly indicated that unless we quit our shopping around and booked right away, there would be no rooms at the inns.

But our investigation found most dire warnings about low availability were dishonest: Most hotels still had plenty of rooms left. We conducted 80 searches for hotel stays in major cities across these eight websites, and all spit out misleading messages. We repeated these searches three times over three weeks. Each time our shoppers got alerts about shortages that typically didn’t exist.

Don’t let warnings like these deter you from shopping around. Even if someone else buys that last discontinued sofa, salespeople are always happy to find something else to sell you.

Fake Competition

Many consumers assume they’re enjoying low prices due to fierce competition among Amazon, Walmart, Target, and other mega-retailers, plus easy-to-compare prices using Google and other search engines.

Unfortunately, as we've discussed in a previous report, that’s usually not the case. In fact, there is little price competition for many big-ticket items like appliances, TVs, computers, bikes, and more. That’s because sellers, in collaboration with manufacturers and online search engines, work hard to limit price competition. It’s one reason the U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Trade Commission, and 50 state attorneys general are now investigating Amazon, Google, and other tech giants.

A common way manufacturers and retailers avoid price wars is by using a “minimum advertised price” (MAP), prohibiting retailers from advertising products for prices below preset minimums. If a product’s MAP is $499, that’s the lowest price retailers can advertise. While it’s still worth shopping around, this means there’s little price competition for many products.

Another way companies with dominant market share present an illusion of competition is by operating several different brands. While it seems like there are dozens of travel-booking websites fighting for your dough—Agoda, Booking.com, Expedia, HomeAway, Hotels.com, Hotwire, Kayak, momondo, Mundi, Orbitz, Priceline, Travelocity, Trivago, Vrbo—all of these and others are owned by either Expedia Group or Booking Holdings.

Lack of competition usually results in higher prices. With hotel bookings, it has led to price agreements between hotels and travel websites that require them to charge the same price for the same room no matter where you shop.

Sellers should set their own prices without agreements or constraints.

Bait-and-Switch

Bait-and-Switch

When travel websites like Vrbo/HomeAway and FlipKey show you per-night rates that don’t include hundreds of dollars in mandatory service fees, cleaning fees, “owner fees,” penalties for “additional guests,” and other poorly disclosed charges, it’s a bait-and-switch. Ditto for hotels that display per-night rates that don’t include their “resort” or facility fees. Although laws and FTC rules prohibit such schemes, enforcement is rare.

The travel industry is awash in hidden fees costing consumers billions each year. Hotels increasingly charge poorly disclosed mandatory “resort” and “facility” fees, padding profits and making price comparisons harder. These extra charges—usually $20–$40 per night—aren’t shown in the per-night rates displayed in search results on travel booking websites, making cheapest-to-most-expensive sorting meaningless. These fees also aren’t disclosed on the initial pricing shown on hotels’ own sites. When Checkbook looked at 205 hotel stays in a dozen U.S. destinations, we found more than two-thirds had mandatory resort fees. On average, these junk fees added $29—an extra 13 percent—per night.

And many vacation-rental sites charge even higher hidden fees. Checkbook’s shoppers pulled 600 listings for a three-night stay on Vrbo/HomeAway and found, on average, hidden fees inflated prices by more than 25 percent, adding an extra $231 for our stay. At one-fourth of the listings, hidden fees added more than $300 to the total cost. We found these types of hidden fees were also commonplace on FlipKey.

Drip Pricing

Similar to bait-and-switch, some companies tout only part of a total price you must pay. Cable TV operators have long promised new customers low prices of $79 a month, but once they add in fees, taxes, and rental fees for things you’d think would be standard—routers, remotes, DVRs, converter box for a second TV, etc.—you’ll pay $150 a month.

Airlines’ prices also appear artificially low since basic economy fares may not include baggage fees, carry-on allowances, seat selection, ability to accrue frequent flyer miles, or the right to cancel or change your trip (even for a fee). The carriers use basic economy prices to lure you in before piling on extra charges for services most travelers want.

Price Line-ups and Decoys

Price Line-ups and Decoys

Most consumers, when presented with a line-up of product models with an array of features and price points, will select one in the middle. Stores often use this tendency to upsell shoppers by showing them seemingly less-desirable or budget options; they know they’ll likely splurge a bit more for a higher-priced model.

Price decoys are a similar tactic to groom shoppers to pay higher prices. Retailers often display a significantly more expensive option—say, a $1,700 necklace—right next to a $500 one to make the lower price tag seem more affordable. Apple, for example, does this with its watches: You likely won’t pony up $1,400 for its top-end Hermes Series 5 model, but that price makes spending $299–$699 on a more popular model seem like a decent value.

Often, when you browse or search retail websites, it looks like products are displayed by default in a somewhat random order, but there’s often no randomness to it at all: The site is designed to show you a few choices to help you feel good about the price you’re willing to pay.

People Also Bought…

A cardinal rule for salespeople is to always have something to sell. If you decide the item you’re considering isn’t for you, websites and stores keep on hand lots of other options you might buy instead.

And sites like Amazon are masters at showing you stuff related to what you’ve searched for to motivate you to keep adding items to your shopping cart.

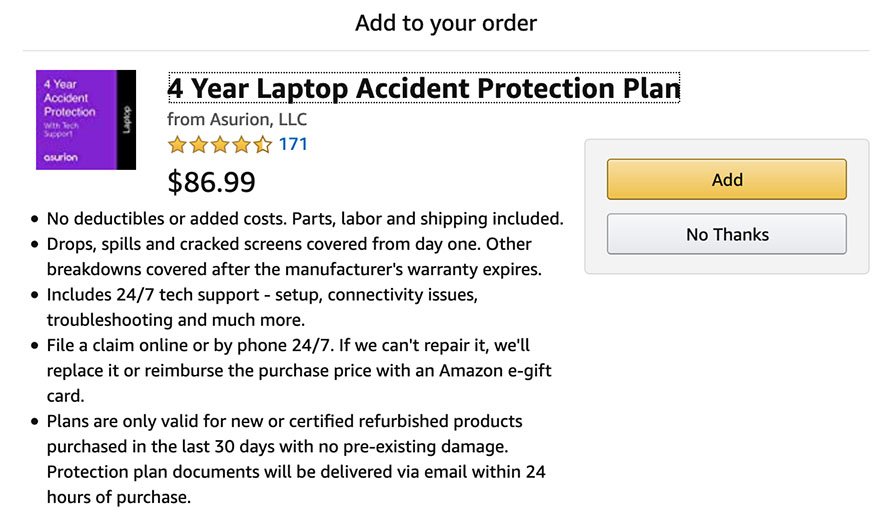

Add-ons

Our loss-aversion tendencies also make us ripe for paying extra to “protect” purchases or our finances. At checkout, sellers often warn about big risks—expensive repairs for breakdowns or accidental damage; natural disasters affecting travel—and then offer to sell you a solution in the form of insurance to protect against these losses.

Checkbook has evaluated these mini “peace of mind” policies, including home warranties, extended product warranties, travel insurance, rental car coverage, and more. We find these plans help their sellers make moolah, but don’t provide much value to consumers. Buy insurance to protect against risks that could be financially catastrophic—house fires, auto accidents, medical care—and not to pay for repairs or replacement products you could easily afford.

Not-So-Independent Referrals

Many companies promise to connect you to the best deals or the best companies. But these arrangements often exist to serve sellers with sales leads and not necessarily help you find the best businesses or lowest prices.

For example, alongside its vehicle reviews Consumer Reports’ website displays prominent messaging such as “Ready to Buy? Save Money with Build & Buy Car Buying Service! Members have seen an average savings of $3,016 off MSRP.” Not-so-prominently disclosed: These links take you to TrueCar, which makes its money by providing sales leads to car dealers. It partners with Consumer Reports, AARP, and many other membership groups and companies that get a cut of fees paid by car dealers to TrueCar when their referrals are used to close deals with affiliated dealers.

TrueCar advertises “Car buying at its easiest,” but when we tested it, multiple car dealers were unleashed on us. After five months, one near-daily emailer even sympathized: “You’re probably saying to yourself...‘Please leave me alone!’”

And TrueCar likely won’t net you the lowest price for your new ride. Although it displays price commitments from participating dealers, we usually find far better deals elsewhere. We advise car shoppers that the best way to get the lowest price is to make dealers bid competitively, which bypasses negotiation hassles and forces dealerships to offer their lowest prices. Here at Checkbook.org, we provide a step-by-step guide on how to do this. And for more than 25 years, we’ve offered our CarBargains service to consumers who want to pay our experts to do this shopping for them.

And TrueCar likely won’t net you the lowest price for your new ride. Although it displays price commitments from participating dealers, we usually find far better deals elsewhere. We advise car shoppers that the best way to get the lowest price is to make dealers bid competitively, which bypasses negotiation hassles and forces dealerships to offer their lowest prices. Here at Checkbook.org, we provide a step-by-step guide on how to do this. And for more than 25 years, we’ve offered our CarBargains service to consumers who want to pay our experts to do this shopping for them.

We find that the prices our CarBargains service obtains beat the lowest ones offered by dealers via TrueCar by an average of more than $1,500 per car—which indicates Consumer Reports’ special “Member Pricing” supplied by TrueCar isn’t really so special.

Renewal Discounts

As we detail in our coverage of auto insurance rates, many drivers pay too much for auto insurance because they stick with the same company year after year. Often it’s because they think they’re getting big price breaks for their loyalty. Don’t assume the rate you’ve paid in the past is still a good price; every few years, shop around.

For a Limited Time Only!

For a Limited Time Only!

Another selling technique is to claim a discount is available for only a short time. Want the lower price? Better get moving as it’s only good on Black Friday or end-of-the-year clearance or Presidents’ Day or Valentine’s Day or Memorial Day or 4th of July weekend… But really, there’s no rush: At most stores, the supposedly temporary “discounts” never end.

Deadlines show up in other high-pressure sales environments: gyms offering to waive hundreds of dollars in initiation fees if you sign up that day; free upgrades that won’t be around after you leave the room.

Salespeople know that if you walk out of the store or their pressure-cooker presentation, you probably won’t return. By setting immediate deadlines, they hope you’ll stop your pesky contemplation and buy already.

Reframing

If a seller knows its customers will balk at paying a big price, it might split it into smaller, more acceptable slices. So when QVC wants to sell you, well, just about anything, it offers it for “5 Easy Pays of $22!”

Lots of non-infomercial retailers also make their prices seem more manageable by offering smaller payments. Kayak even offers to let you make monthly payments for trips.

By Design

Online and brick-and-mortar stores spend millions consulting with behavioral psychologists to get you in the mood to buy. Certain colors and fonts can play huge roles in framing products as affordable or as luxury necessities. Piping in slow or classic tunes makes you linger as you browse; many restaurants play fast-beat music so you’ll chew quickly. Department stores change up flooring materials to slow your gait. Some shops even spray scents formulated to move merchandise.

Sssshhhh…Just for You

“Because you’ve been a great customer...” “Because we have a crew working nearby…” “Because we have leftover materials…” “Because you’re a parent or a senior…” “Because you belong to the Moose Lodge…” Salespeople know if they can convince you that you’re getting special treatment, you’ll feel good about their offers—and might not shop around to find better prices or terms.

Payment Mediums

Many companies have taken a cue from casinos’ use of chips by pushing alternative payment methods. For example, using Starbucks’ app to pay for daily $5 lattes feels like you’re not spending real money.

Loss Leaders

Loss Leaders

Grocery stores excel at advertising a small number of items at steep discounts to make customers think they’re getting low prices. Of course, once you’re in the store you’ll pick up several other things in addition to that BOGO ice cream.

We find most other sales are really fake discounts off “regular” prices that you’ll rarely pay. And even legit price reductions are often just a way to get you in the door. Although most Black Friday prices now aren’t really special, some stores still throw out deals like 50 laptops for $199 and splash that price across their ads—and perhaps even get some free publicity for it (for some reason, news media treat misleading after-Thanksgiving marketing campaigns as breaking news). But their real strategy is to create the impression that all their prices are super-low, luring you in to buy other stuff.

Store Layout

There’s a reason you have to walk a mile for milk at most grocery stores: You’ll pass by impulse items, free samples, baked goods, and other displays designed to make you pause and pick up other stuff while there.

Non-supermarkets also carefully display products. High-profit items are usually at eye level. And the best bargains are usually right at the entrance, so you’ll get the impression that the deals continue as you travel deeper into the store.

Free Gifts and Cross Promotions

For some reason, most of us would much rather avoid losing something than pay for something, even if the two things are of equal value: For example, losing a $100 bill feels far more painful than buying something for $100. Marketing pros take advantage of this “loss-aversion” tendency by presenting sales prospects with offers to make customers feel like they’ll lose money or an opportunity if they don’t act. A common ploy is offering gift cards for future purchases, rather than discounting the thing you’re buying. Those “gifts” are engineered to put you back in the store, spending money—usually more than the value of the gift card.

Bundles and Package Deals

Package deals work on our tendency to pay one price for several different products or services rather than spring for each separately. Vacation packages, for example, are attractive because of their simplicity: In our minds a single all-inclusive price “shrinks” the price of the whole deal, making it seem more affordable.

Online retailers often offer bundles, especially for electronics. Once you’ve agreed to pay $1,500 for a new laptop, you’re easy prey for them to push a docking station, printer, or software. After all, one of these extras will only cost another $100, which is not much money compared to the $1,500 you’re already forking over.

Loyalty Programs

Loyalty Programs

Airline miles, credit card points and rebates, hotel status tiers, Starbucks stars, buy-10-get-one-free offers, platinum-level memberships, school rewards from supermarkets—all are carefully designed to manipulate you to spend often and more.

Low-price Guarantees

Many sellers promise to reduce a price if you later find the items for less, and Checkbook’s researchers easily got stores to honor price-matching policies. But though these promises seem customer friendly, they often serve only to provide customer confidence in prices, or even cover for a store’s high initial prices. One study found that 75 percent of tire sellers with price-matching guarantees charged higher prices than direct competitors without such guarantees, according to Utpal Dholakia, a professor of marketing at Rice University.

Clearance!

We often read advice that argues there’s a best time of the year to buy something because sellers need to clear out old inventory—for example, wait until the end of summer to buy a new grill or lawnmower. We find these claims are generally without merit. Often our shoppers find “clearance” items available for the same price from the same sellers months later.

Word Play

Word Play

Marketing experts avoid adjectives near price displays that might conjure a feeling of high cost. So instead of using “Big savings” or “Highly rated” or “Great performer,” they’ll say “Sale” or “Best seller” or “As advertised.”

Prestige Pricing

While some stores and brands offer continuous fake sales, others—usually luxury lines of perfume, luggage, jewelry, etc.—rarely if ever allow any discounting. The idea is to make you think it’s okay to pay exorbitant prices for their products. Many luxury brands also de-emphasize prices as much as possible. For example, Tiffany’s desktop website doesn’t show you prices until you click on or hover over individual items, and even then its prices are displayed in a tiny light font, as if what you’ll pay is unimportant.

Buying in Bulk

We’re conditioned to believe buying in bulk saves money—and sometimes it does. But often buying more means we’ll spend more than planned, or that we’ll waste savings when throwing out 40 fish sticks no one ate.

Even non-warehouse stores motivate buyers to buy in volume. A popular tactic is setting thresholds shoppers can meet to qualify for discounts. If a store offers you an extra $25 in savings if you buy $100 of stuff, you’ll likely keep adding items to your cart to reach that goal.

Charm Prices

We all know that stores display prices ending in 99, 98, or 95 to make prices appear lower—$9.99 is perceived as “$9 and change,” rather than $10. It’s actually not the “99” or “95” at the end of the price that affects us—it’s that shoppers pay most attention to the left-most numbers in a price; $199 seems a lot better than $200.

Also effective is pricing using seemingly random amounts—say “$328.46.” This makes it look like prices were carefully set so they are as low as possible.

Easy Math

Some sellers, especially those with pricey products, advertise discounts as nice round dollar savings (“Save $100”), rather than as a percentage off. The idea is that you’ll more easily absorb the supposed deal.

4 for $10

We all fall for this. You’ll buy four of them, even if you can buy just one for $2.50.

Invading Your Privacy

Invading Your Privacy

We saved the worst for last. Your phone, web browser, internet service provider, cable TV operator, software, mapping apps, vehicle, social media accounts, credit card companies, grocery stores, favorite retailers, smart home devices, and others scoop up a slew of info about where you go, what you search for, who you interact with, what you buy, how you buy it, how much you spend, what you read, how much you borrow, what you watch, how fast you drive, and more. They then sell and trade it for marketing purposes. Search the web for a new sweater and for days afterward you’ll likely get an onslaught of targeted sweater ads.

There’s no clear disclosure of what data these companies collect and what they can do with it. When you agreed to its terms of use, did you realize your phone would collect and sell where you traveled every day? Likely not. And lots of companies are making lots of money buying and selling our data that’s being used in ways we never really agreed to.

Worse, there’s not much we can do to stop it.

On January 1, 2020, the California Consumer Privacy Act went into effect, which gives its residents some rights over their data collected by Google, Facebook, brokers, and the like. It’s similar to the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation and is a victory for U.S. consumers—even non-Californians. The law requires businesses to explain what info they collect and why; and because it’s easier to implement systems just once, many offer the same opt-out rights that they do for customers in California.

But because the law requires consumers to take charge of their data, it won’t have much impact unless most consumers advocate for themselves—and businesses that collect and sell these data are counting on that not happening.

Companies are increasingly finding ways to collect data that most of us don’t want them to have. When you submitted your spit to learn about your ethnic heritage, did you think that 23andMe would also sell your entire genome to researchers? Are you comfortable that several companies pay to know your exact whereabouts at all times? If laws are changed and health insurance companies are once again allowed to use pre-existing conditions to set their rates, will they buy data available from brokers—that you unwittingly supplied for free—to deny you coverage?

Our lack of privacy rights isn’t just about ads for sweaters.

In 1959 as a freshman in high school, I had a part time job in a large local department store. I printed signs and labels in an attic room set up for printing. One thing I did was to print both large and small individual price labels for individual items such as shirts and sweaters. With some I had to print the price labels and then use a red ball point pen to cross out the printed price and by hand print the sale price. I delivered them to the departments where sales people had to attach them to the unlabeled articles on sale.

ReplyDelete